October is National Principals Month: The Impact of a Principal is Even Greater Than We ThoughtBy Jim Lynch, Executive Director, Association of Wisconsin School Administrators (AWSA) The work you do is a big deal! Research since the 1990s has demonstrated that school principals' effect on students contributes to 25 percent of the total school influences on students’ academic performance. A report released earlier this year from the Wallace Foundation leverages two decades of research to demonstrate that principals are even more important to students and schools than previously thought. In the report, How Principals Affect Students and Schools: A Systematic Synthesis of Two Decades of Research, researchers concluded the following: “Principal impact on student achievement has likely been understated, with impacts being both greater and broader in affecting other important outcomes, including teacher satisfaction and retention, student attendance, and reductions in exclusionary discipline.” At a time when only 1 in 4 principals stay in a given leadership position longer than 5 years while research tells us it takes 5 to 10 years for a principal to have a meaningful impact on a large school, this report is an important reminder that district’s have an enormous interest to attract, retain and continually improve strong school leaders. In their review of the literature on this subject, the authors determined that school principals operate in four overlapping “domains” that influence school outcomes. Each domain includes leadership behaviors that coalesce into the outcomes school leaders, educators, families, and communities seek to achieve in their schools.

1) Engaging in Instructionally-Focused Interactions with TeachersA key role for principals has always been providing instructional leadership to teachers and staff. The authors, however, argue that the definition of “instructional leadership” is too broad and that their “synthesis emphasizes that not all instruction-related activities are productive ones” (p. 59). Rather, “high-leverage instructional activities appear to be those that support and improve teachers’ classroom instruction.” To that end, the authors’ group these activities into the three buckets of teacher evaluation; teacher feedback, coaching, and professional learning; and the use of data toward instructional improvement. When it comes to evaluating teachers, there are two evidence-supported ways principals can make the process effective. The first is getting buy-in to the process from teachers and staff. When educators feel there is a significant level of legitimacy and purpose to evaluations, they tend to take them more seriously. This, in turn, leads to greater professional growth. Secondly, a sound, well-understood process can help principals implement teacher evaluation, especially when engaged in teacher observation. While the time spent on evaluations is important, what appears to be even more critical is the validity of the scores principals give educators on their evaluations. One of the challenges in conducting evaluations is that principals typically can accurately determine who are the top and bottom performers among their teachers and staff. They tend to have a more difficult time identifying and providing meaningful feedback to teachers in the middle. In the area of providing feedback, coaching, and professional learning, the Wallace Foundation study found increasing evidence for the positive role principal feedback plays in the performance of teachers and, ultimately, student achievement (p. 61). The authors highlight research that examined data from Miami-Dade County Public Schools. According to that study, “time spent on coaching teachers is associated with higher student achievement growth, whereas time spent on informal classroom walk-throughs is unproductive, especially in high schools” (p. 62). In recent years, principals increasingly have been expected to collect and analyze data to support instructional strategies and school improvement efforts. The research examined by the Wallace Foundation supports this, finding that “effective principals make use of data not only to make good decisions and address school needs but to inspire action” (p. 63). To establish a data-driven culture in their schools, principals should consider engaging teachers and staff in the process through so-called “data chats” and regular updates. This allows teachers to become accustomed to key data points and how they can leverage them to improve their own performance and student achievement in their classrooms.

2) Building a Productive ClimateThe authors of the Wallace Foundation report define school climate broadly, as the set of circumstances that influence school culture, academic achievement, and teacher performance. A strong school climate is one in which there are high levels of “collaboration, engagement with data, organizational learning, a culture of continuous improvement, and academic optimism” (p. 64). When principals are successful in establishing a successful school climate, the effects can be long-lasting. This is true even in schools with high needs, where the creation of a positive climate has been shown to be self-sustaining, even long after the change agent principal has left. Furthermore, in schools that have positive professional climates, teachers tend to reach greater levels of professional development and growth (p. 64).

3) Facilitating Collaboration and Professional Learning CommunitiesWhile the authors acknowledge that collaboration is part of a school’s climate, they placed it in a separate category to highlight its particular importance in fostering high levels of instruction and educator performance. A key way successful principals encourage collaboration is through data-driven academic improvement efforts. By setting “purposes and expectations,” they can empower teachers and staff to leverage data for their own professional learning and training. Naturally, professional learning communities (PLCs) are highlighted as a common way in which principals facilitate collaboration. Evidence suggests that PLCs, when done well, can support a positive school culture, elevated professional development, and effective supports for instruction (p. 67). As outlined in the Wallace Foundation report, “Principals who are effective instructional leaders provide time and support for PLCs. They work with teachers to create a shared sense of responsibility for student learning. They engage directly to facilitate teachers’ collaborative work in their instructional teams. They also schedule and budget with opportunities for professional learning in mind” (p. 67).

4) Managing Personnel and Resources StrategicallyThe fourth and final domain the Wallace Foundation authors identified in their analysis focuses on all the ways in which principals are charged with managing their schools’ assets—including those that are tangible and intangible. Intangible resources for principals include their time and external social capital. School leaders with strong time management skills have more time to spend on observing and evaluating educators than their peers with less-defined skills. Additionally, principals who take the time to build relationships with their families and other stakeholders tend to be associated with schools with higher reading scores and teacher satisfaction. The more tangible resources principals must manage include school budgets and personnel. According to the authors, “Within organizational management, research most clearly connects strategic personnel management to student achievement and other positive outcomes’ (p. 68). Personnel management includes hiring staff, assigning and placing staff, and ensuring high levels of staff retention and satisfaction.

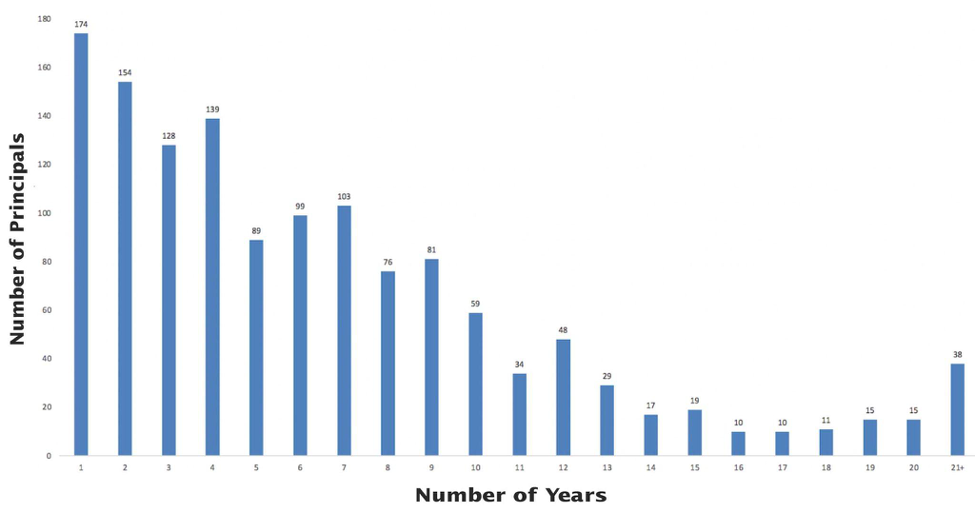

Early Career Principals According to the School Leaders Network, only fifty percent of brand new principals make it past year three. Considering that almost one-third of Wisconsin principals are in their first three years in administration it is critical to ensure that our new leaders have the support necessary to successfully launch their leadership careers (See Table A).

Table A: WI Principal Years of Experience, from 2019-20

Growing District Capacity to Support Principal Excellence School administrators need skillful support from district leaders. The WASDA-AWSA Supporting Principal Excellence Academy is offered each year for superintendents, and other district leaders who directly support principals to strengthen the support system for leadership excellence.

Read more at:

|