Using Data to Inform and Support a Coaching System

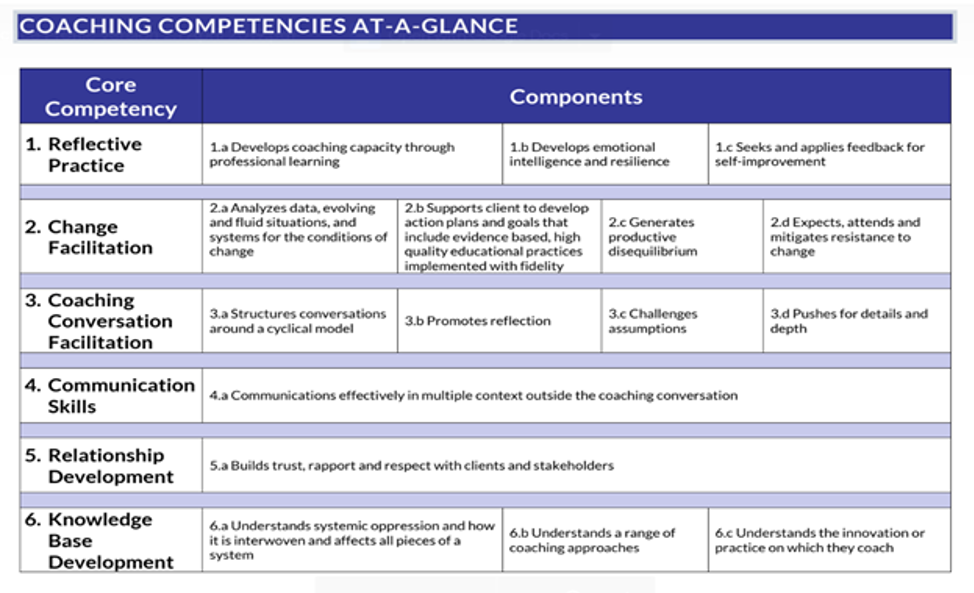

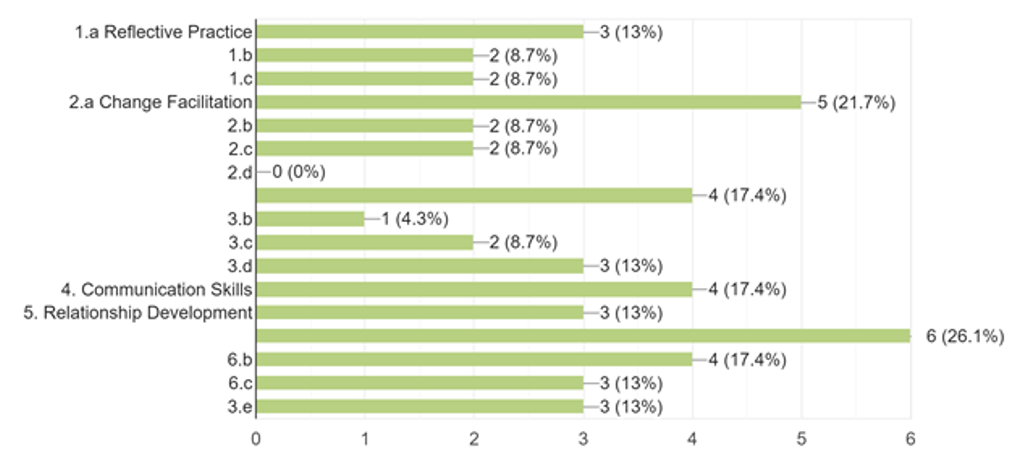

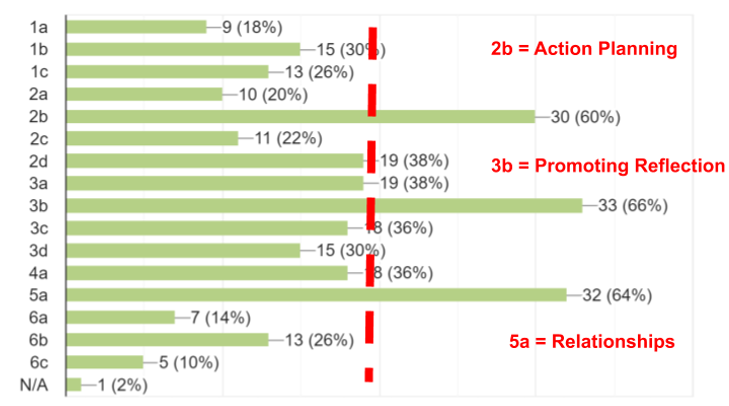

by Rachel Fregien Over three years ago, the Department of Public Instruction introduced the Coaching Competency Practice Profile (CCPP), which provided the field with a consistent definition of coaching. You can read more about how the document was developed and its intended use here. Since that time, a diverse group of stakeholders have been busy developing tools and resources supporting the foundational definition of coaching to support the growing practice of educational coaching across the state. As the formal practice of coaching in education has expanded, there is a growing need to provide meaningful and relevant feedback for coaches that supports guided, individualized, and self-determined professional growth and development. Recent requests from the field consistently include a need for coach-specific professional growth and development tools. Many coaches report they are being evaluated using teaching frameworks that do not fully match the tasks completed or responsibilities held. Using the Coaching Competency Practice Profile (CCPP) as the cornerstone document was the logical place to start because it provides a framework for providing relevant professional development and growth opportunities. The first step for any coach is to understand where their professional growth needs are. A coach’s review is based on the coaching competencies and corresponding components outlined in the table below. After a coach reflects on their professional practice, the results help in developing coaching goals and facilitating coaching conversations. The self-review informs professional learning in two ways. First, it provides a starting place for coaches to set their own growth goals. If, for example, an individual coach rated themselves lowest in competency 6, Knowledge Base Development, they would want to take a closer look at each of the three components to see if there was one component where they self-assessed exceptionally low, or if they rated themselves lower across the entire competency. This then prompts the coach to consider where best to focus their professional learning. Additionally, in systems where there are multiple coaches, this data can be collected anonymously to direct a district or building system of professional learning for coaches. Trends and patterns from all coach responses can be analyzed and used to meet professional development the needs of the coaching system. For example, the following dataset shows 26 percent of coaches created a goal related to competency 6a, which is “Knowledge Base Development - understanding systemic oppression and how it is interwoven and affects all pieces of a system.” “Change Facilitation” (CCPP 2a), which is analyzing data and evolving and fluid situations for the conditions for change, is another component that rises to the top, making up almost 22 percent of the coaches’ goals. A system would use this data to inform the scope and sequence of monthly professional development and coaching supports offered to the coaches within their system. By using the data from Figure A, learning is intentional and connected to need. Figure A

Coaches who analyze and reflect on their own practice understand their professional strengths as well as areas in need of development. Personal self-reflection allows the coach to consider how the needs of the coach’s clients can, and do, connect to the larger goals of the school and district. A growth mindset is as important for the adults in the school as it is for the students, and applying goal-setting as part of a cycle of continuous improvement helps to align priorities and maximize impact. The data presented in this article represent coaches across the state of Wisconsin and demonstrate how this data can be used to inform and support a coaching system. These coaches are working directly with the Department of Public Instruction through special education discretionary grant funds. Through the work of this grant, 12 regionally-based coaches support 11 district-level coaches and make up a statewide network of coaching supports. As the self-review tool gained popularity, it became clear that the field wanted more. It was evident that the need for a systematic assessment of thecoaching system was growing. As a response, multiple data collection tools, resources and guidance on how to use these resources to inform a coaching system were developed. They were piloted using various grants and are now being utilized in districts and buildings across the state. An anticipated challenge will be to measure the impact of practice for coaches. It is not enough to strive to improve practitioner knowledge, strategies, and implementation of practice. Improved practice is meaningless unless it leads to improved impact on student success. While we cannot make a direct correlation between student outcomes and coaching, research exists connecting improved teacher practice to improved student outcomes. Furthermore, the research outlined below demonstrates a relationship between coaching and student outcomes.

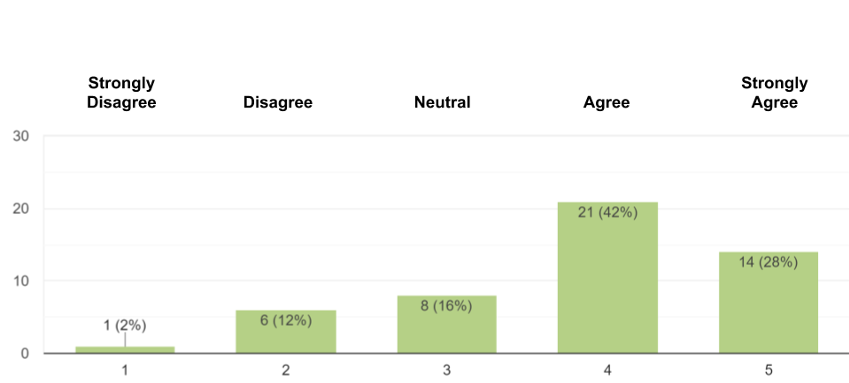

While we cannot make a direct correlation between student outcomes and coaching, research exists connecting improved teacher practice to improved student outcomes.After a system understands the trends in the needs of coaches, additional tools can be introduced to aid in the continued support and individual coach growth. The coach reflection log is a tool that tracks progress of coaching and provides relevant data to drive a coach’s own practice and future professional development opportunities. Coaches who use the reflection log do so after each unique coaching session. For example, if a coach meets with a team twice a month and three individual educators twice a month, they would complete the reflection log for each of the ten coaching sessions. The prompts in the tool ask the coach to reflect on several aspects of their coaching session. The first question asks coaches to reflect on the strategies they used in the coaching session and how they connect and reinforce their personal PPG. Not only are coaches focusing on the goals of their clients, they have their own growth goals at the top of mind throughout their coaching sessions. The data in Figure B shows that 70 percent of the time, the coaches who complete the self-reflection tool reported they “agree” or “strongly agree” that the coaching strategies they use reinforce their professional practice goal. This means that 70 percent of the time, the coaches felt like they could “see” their own growth goals within their coaching sessions. This is evidence that the coaches are actively engaged with their professional growth and considering it within their coaching practice. Figure B

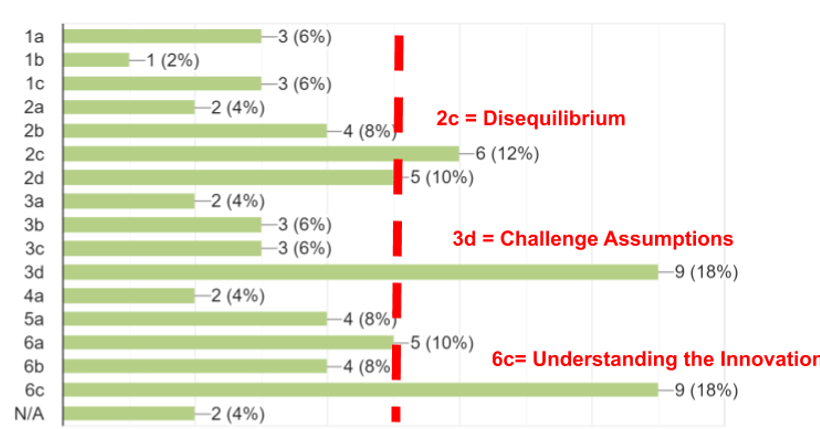

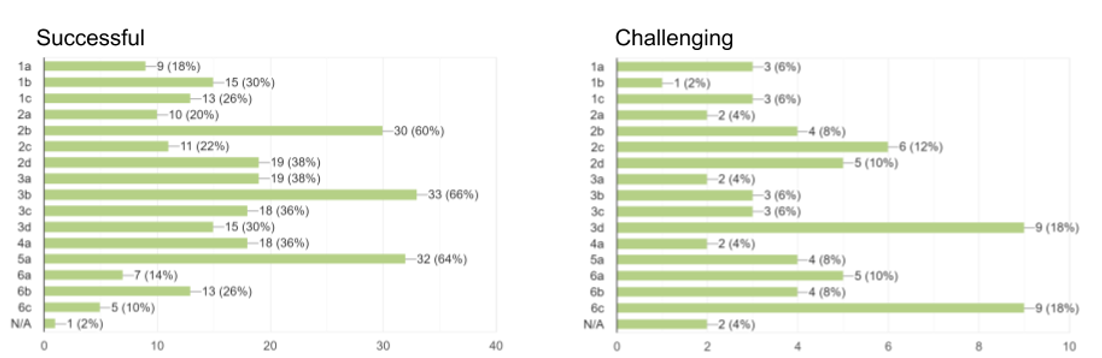

Next, coaches are asked to select any of the coaching components that they used successfully during each unique coaching session. This question leads coaches to reflect upon successes and celebrations within their sessions. Figure C represents coaches’ responses to this statement: “Select any of the coaching components that you used successfully during your coaching today.” Out of 50 unique coaching sessions, three components rise to the top of the responses. Coaches are most often reporting that action planning (CCPP 2b), promoting reflection (CCPP 3b), and developing relationships (CCPP 5a) are going well within sessions. Figure C The study of this data validates the system’s efforts in supporting coaches in the implementation process. This data reflects the first four months (September-December 2019) of the coaching relationship. In these first few months, teams and coaches are asked to create an action plan and develop monthly agendas. Based on the primary data related to professional growth goals, an effort was made to support the coaches through monthly training and coaching with specific focus on competencies 2 and 3. Professional development focused on coaching cycles and action planning. Coaching support centered on practicing cyclical coaching conversations while promoting both self and client reflection. Therefore, it is no surprise that coaches are experiencing success in these areas. Conversely, coaches are asked to reflect upon the components that they should have implemented, or those that were challenging to implement during each unique coaching session. This response item is of particular interest to a system. The data can be indicative of coaches feeling unprepared or inexperienced to lean into the particular competencies. It can show a system where there are gaps in experience, confidence, or overall support. Figure D depicts how coaches responded to the statement: “Select any of the coaching components that you should have implemented, or were challenging to implement during your coaching today.” Figure D Out of the 50 unique coaching sessions, three components stand out. It is important to note that the data in the following graph represent the first four months of the coaching relationships. Coaches most often reported challenges or barriers related to creating productive disequilibrium (CCPP 2c), challenging assumptions (CCPP 3d), and understanding the innovation on which they coach (CCPP 6c). Due to the nature of a coaching relationship, coaches may have avoided or had difficulty leaning in on creating productive disequilibrium (2c) and challenging assumptions (3d). At the beginning of a coaching relationship, coaches often focus on developing rapport and creating an atmosphere of safety and trust prior to leaning in and coaching heavy. However, it is equally, if not more, important for this data to be critically considered from a systems lens. It is evident from the data that coaches may not fully understand the innovation around which they coach. As a response, professional development and coaching support around the innovation may need to be enhanced. Questions related to training relevance and effectiveness should be addressed to meet the needs of the coaches within this system. Finally, when analyzing the data side-by-side, one will notice there are fewer overall responses related to the challenge prompt as compared to what was successful. Figure E

This is promising data. It suggests coaches are experiencing more celebrations than challenges. Implementing an aligned and cohesive coaching system of support is no simple task. Taking the time to explore how best to support coaching at a system level saves time and money and improves the chances for success. Looking at the coaching system from multiple perspectives will provide a proactive plan to support the coaching system and determine the extent to which coaching meets the needs of the community. Contact: Rachel Fregien Read more at:

Elementary Edition - Secondary Edition - District Level Edition

|