High-Leverage Practices in Special Education as a Foundation for Improving Student Outcomes

by Daniel Parker, Assistant Director of Special Education, Wisconsin DPI In 2014 the Council of Exceptional Children (CEC) with support from the CEEDAR Center, began work on developing High-Leverage Practices in Special Education. In 2016, twenty-two high-leverage practices were finalized and are now being widely utilized by higher education and others to ensure each and every special education teacher has a foundational understanding of practices relating to assessment, IEP development, and provision of specially education services. CEC selected practices that occur with high frequency, are research-based, broadly applicable, and most importantly can be clearly articulated and taught to any educator. This article breaks down highlights of these practices, provide tips on how school principals can support special educators in utilizing the practices, and shares additional WI DPI resources that align with these practices. To access more complete resources on these practices, the CEC and CEEDAR Center have made this information available for free online at: https://highleveragepractices.org/. This web page includes a downloadable guide and documents describing all 22 of the special education high-leverage practices as well as additional resources that include videos, webinar recordings, journal articles, and other tools, presentations, and reports. The IRIS Center has also developed free online modules further outlining the CEC High-Leverage Practices in Special Education. It should also be noted that Division for Early Childhood (DEC) also developed a companion set of high-leverage practices for Early Childhood. Rational for Schools to Explore and Discuss High-Leverage Practices in Special Education

The CEC twenty-two High-Leverage Practices in Special Education fall into four areas:

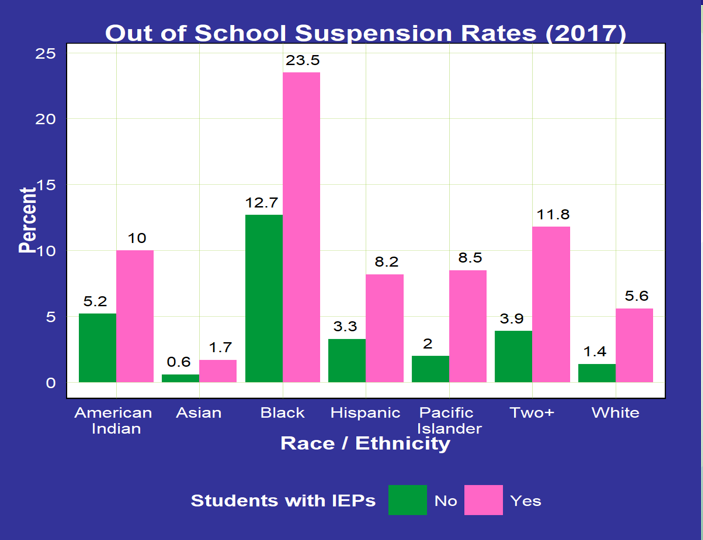

Although these practices are broad enough to be useful to general education teachers, the authors specifically identified aspects of these practices that are needed to provide individualized supports based on each student’s unique disability-related needs. In addition, although all teachers require skills in data analysis, collecting information, collaboration, meeting facilitation, and instruction, these skills as applied to special education teachers often takes on a deeper level of individual connection, problem solving, and monitoring progress to support accelerated learning and growth. Assessment Assessment is comprised of 3 practices that focus on comprehensive understanding of individual student strengths and needs, interpreting and sharing information with others, and using assessment to analyze progress and make adjustments that improve student outcomes. Successful application of these practices should assist IEP teams to ensure students are appropriately identified for special education, i.e. addressing racial disproportionality in special education, as well as conducing comprehensive special education evaluations that understand student assets and skills as well as specific areas related to individual disability-related needs. In addition, these practices require special educators to have a deep understanding of the types of data, information, and formal and informal assessments that can be utilized to explore student strengths and needs. How Principals Can Support Assessment Practices Principals should assist special educators in ensuring that they have all of the data and information available through each student’s equitable multi-level of support so that information from general education interventions and positive behavior supports are easily accessible to be included in initial evaluations, re-evaluations, and annual IEP meetings. In addition, at the onset of special education evaluations, principals can encourage a thorough review of existing data meeting or other communication channel between all members of an IEP team, including parents and general education teachers, to discuss what information is known about a student prior to conducting any needed additional assessments. The review of existing data is a required component of a special education evaluation and when done efficiently leads to improved family engagement, concise data collection and interpretation, and improved identification of disability-related needs. Finally, principals can support ongoing assessment by ensuring every special education teacher has a system of monitoring progress of IEP goals so that data can be reviewed and reported by the IEP team at any time to identify if students are making progress on annual goals and closing achievement gaps compared to classroom peers without IEPs. DPI Additional Resources for Assessment The DPI special education team will be hosting a webinar on monitoring progress of IEP goals on November 21st that will be recorded and posted to the CCR IEP Learning Resources web page. Additional resources on monitoring progress of IEP goals can be found through the CCR IEP Step 5: Analyze Progress webinar, slide deck, and at a glance document. DPI is also in the progress of developing a Comprehensive Special Education Framework that will assist IEP teams with conducting special education evaluations focused on identification of individual student needs. A new web page will be launched this winter with slide decks and other resources. Finally, DPI supports The Network that works with preK-12 educators, schools, districts, and other community partners to reduce racial disproportionality in special education through a multi-tiered system of compliance activities and improvement supports. The Network offers free and low cost trainings on topics relating to social justice and reducing racial disproportionality. Collaboration Collaboration is comprised of 3 practices that focus on collaboration with professionals, facilitating meetings, and family engagement. Special education teachers are often in the sensitive role of engaging in discussions about significant academic and functional/behavioral needs of students with others who may have strongly held beliefs, experiences, and ideas on how best to support individual students. This requires not only listening and interviewing skills but also facilitating conversations across IEP team members on the best way to provide services and supports based on individual student needs. Special education teachers not only support students, but also other provide support to educators and families who may be trying something new or unknown. Thus, special education teachers not only help students be ready for the world but often find themselves helping others to be ready to support students entering classrooms. Communication for special education teaches often takes many forms and environments including co-teaching and co-serving environments as well as coordination with home and community supports and at times other agencies and organizations. When working with paraprofessionals, general education teachers, and other school staff, special education teachers may also have to utilize coaching skills to support others in the use of supplementary aids and services (i.e. accommodations) or implement behavior intervention plans as outlined in a student’s IEP. How Principals Can Support Collaboration Practices Principals often have influence on teacher schedules that support collaborative opportunities for meeting, professional learning, and connecting special education teachers to general education curriculum, resources, and discussions related to grade level standards. For special education teachers to be successful, they must have a solid understanding of grade level standards and classroom expectations so that they can best assist IEP teams in identifying specific disability-related needs (i.e. skills) that students need to improve to be successful in the school community. Principals can ensure general and special education teachers have time each day to build relationships, learn together, and share ideas about student learning. In addition, principals can assist special education teachers with linked to learning family engagement strategies through IEP team meetings. This may include talking with families about strategies they can use at home to support academic and functional/behavioral needs of students related to IEP goals. Family engagement also means taking time in IEP meetings to learn from families about their hopes, dreams, and fears for their child as well as learning what families already do at home that can be used at school to support learning and engagement. DPI Additional Resources for Collaboration To assist with IEP meeting facilitation, the Wisconsin Special Education Mediation System (WSEMS) provides several resources to support IEP teams, including the ability to request a trained, impartial, professional facilitators to assist with IEP meeting facilitation. In addition, WSEMS, has an online module on Friendly and Productive IEP Meetings that can be a resource for special education teachers and LEA representatives to improve how they conduct IEP meetings. For special education teachers interested in learning communication, listening, and problem solving skills, the Wisconsin RtI Center offers training and resources on transformational coaching that may assist special education teachers in both problem solving and helping others understand student needs when talking with families and colleagues. In addition, DPI has a coaching resources web page that includes a coaching practice profile as well as a recently released inclusive communities web page that includes a practice profile to support inclusive special education practices. DPI also has a co-teaching web page with resources and will be releasing a new co-teaching practice profile later this school year. Finally, there are numerous resources relating to family engagement from WI DPI special education team as well as resources from statewide family support and advocacy organizations including WSPEI, WI FACETS, WI Family Ties, as well as resources to families who have children with special health care needs requiring medical or community supports through CYHCN and Family Voices of Wisconsin. Examples of resources include resources for families to share information about their child at IEP meetings and a monthly special education family engagement newsletter. Social/Emotional/Behavioral Practices Social/Emotional/Behavioral is comprised of 3 practices that focus on providing feedback to support learning and behavior, teaching social behaviors, and conducting functional behavioral assessments. Perhaps more than ever, supporting social and emotional growth and mental health is critical for the academic success of students with IEPs. In addition, educators today can choose from a number of research and evidence-based practices, frameworks, and curriculums that support social and emotional growth that meet the individual needs of students. For students with autism, there are free online modules for educators to support behavior needs such as Autism Internet Modules (AIM) and Autism Focused Intervention Resources and Modules (AFIRM). In addition, access to mental health and trauma informed care resources are highly available through conferences, workshops, and online resources for teachers to learn about effective strategies to support behavior. In addition to learning specific strategies and implementing social and emotional programs, special education teachers are encouraged to help other educators understand the unique assets, interests, and skills a student with learning and behavior differences brings to the classroom. Using social/emotional/behavioral practices, both special and general education teachers can help foster a sense of belonging in the school community for students with different abilities. How Principals Can Support Social/Emotional/Behavioral Practices Principals are a gateway to creating a culture of tolerance and a sense of belonging for each and every student in a school community. Principals can model social and emotional strategies, assist general education teachers to incorporate social and emotional competencies into existing curriculum and instruction, and support special education teachers and IEP teams in utilizing grade level social and emotional competencies as part of the IEP planning process. For example, the WI DPI social and emotional competencies can be utilized as a resource to identify grade level “functional” expectations. Principals can also support a school’s orientation, understanding, and system for out of classroom behavior referrals. In Wisconsin, students with IEPs are disproportionately disciplined and the rate of exclusionary discipline is higher for students of color. Principals should ensure all staff have a culturally responsive lens when determining what leads up to a removal from instruction. Principals can help staff identify subjective versus objective behavior concerns, help staff identify root causes of behavior, and assist educators in clarifying behavior expectations as well as changing adult instruction, supports, or class routines to foster a safe and supportive learning environment for all students. Principals must ensure that students with behavior needs have positive behavior interventions and supports included in their IEPs to support specific disability-related needs. For students who require additional support, positive behavior interventions and supports may include both skill instruction (e.g. learning a specific social or regulation skill) as well as providing supplementary aids and services (e.g. accommodations to reduce stress, allow for movement, provide visual support, or allow choices for student engagement). Many accommodations that are required to be provided per a student’s IEP may also be seen to benefit students school-wide when incorporating Universal Design for Learning guidelines. Utilizing UDL may assist with providing needed supports in the IEP while reducing stigmatization, generalizing the use of supports in the general education environment, and providing supports that benefit all students. Principals must also be aware of legal protections for students with behavior needs and ensure all staff, both general and special education, are aware of these legal protections. Finally, principals can support compassion resiliency for staff that work with high need students who may engage in behaviors that can lead to stress and burn out over time. DPI Additional Resources for Social/Emotional/Behavioral Practices Several WI DPI bulletins provide information on legal requirements relating to discipline, manifestation determination, shortened school day, and providing a Free and Appropriate Public Education. In addition to bulletins, DPI has web resources regarding the appropriate use of seclusion and restraint in schools that includes a module schools can use to analyze data to reduce seclusion and restraint in schools. In addition, in spring 2020 DPI will be updating and adding to web resources for conducting Functional Behavior Assessments (FBA). There are also a number of proactive resources special and general educators can utilize to support social and emotional learning, trauma sensitive schools, and intensive supports for mental health. For those seeking to understand students and families with different backgrounds, DPI supported the development of Wisconsin’s Model to Inform Culturally Responsive Practices. Finally, resources for staff to support compassion resiliency can be found both on DPI web page and through our partnership of the compassion resiliency toolkit. Instructional Practices Instructional practices make up 12 of the 22 high-leverage practices in special education and focus on a wide variety of practices that describe “how” instruction is provided to students with IEPs. These practices address both academic and functional needs of students and includes practices such as identifying short and long term learning goals, designing instruction to support goals to promote generalization, adapting curriculum and materials, using cognitive and metacognitive strategies, scaffolding supports, using explicit and intensive instruction through flexible grouping, engaging students in learning, and use of assistive technology. Although the downloadable CEC High-Leverage Practices in Special Education guide only provides broad information about each practice, special education teachers are encouraged to examine the practices, consider which ones they are proficient and which they may need to improve, and seek out additional training, coaching, and evidence-based practices that provide additional specificity for implementing these practices. Special education teachers can also meet through professional learning communities to identify more specific evidence-based practices, curriculum, or supports they utilize and map these onto the CEC high-leverage practices. For those seeking a deeper level of understanding about these practices, the Council for Exceptional Children published a companion book titled High-Leverage Practices for Inclusive Classrooms ©2019, that breaks down all of the 22 high-leverage practices into more detail, examples, and research base. How Principals Can Support Instructional Practices For teachers to become proficient in any practice, research indicates that coaching is a necessary component. Once special education teachers identify specific practices where they need support, principals can provide coaching resources (e.g. networks of special education teachers or supervisors, mentor teachers, instructional coaches) as well as provide time for special educators to engage in coaching conversations utilizing coaching frameworks to support continuous improvement in specific areas of practice. Similar to supporting collaboration, principals should also ensure special education teachers have opportunities to unpack grade level standards to help them understand how to apply the special education high-leverage instructional practices to support attainment of grade level expectations. Principals can also ensure that special and general education teachers are up to date with available assistive technology supports that can be used either universally for all students as well as for an individual student’s IEP needs. Finally, principals can help support a school’s collective understanding of equity such that each individual student gets what they need, when they need it, in the way they need. Understanding equity as it relates to people with different abilities is a particularly important belief system to have in place to ensure supplementary aids and services (e.g. accommodations and modifications) are available in general education settings and are providing by any staff in the building. DPI Additional Resources for Instructional Practices For special education teachers interested in coaching training, the Wisconsin RtI Center offers training and resources on transformational coaching skills that may assist special education teachers with coaching conversations to support problem solving with families and other professionals. To support reading instruction, DPI has an online module Teaching Our Readers when they Struggle that includes information on how to select interventions. For other instructional practice supports, educators can also explore effectiveness of evidence based practices through national non-profit organizations such as OSEP Ideas that Work, What Works Clearinghouse, IRIS Center, American Speech Hearing Association (ASHA), National Technical Assistance Center on Transition (NTACT), National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders (NPDCASD), Doing What Works, the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), and National Center on Intensive Intervention (NCII). In closing, it is important to keep in mind that the twenty-two CEC High-Leverage Practices in Special Education focus on knowledge, skills, and habits that special education teachers can utilize to support student outcomes. These practices do not address other necessary systems of support such as how students with IEPs are supported through an equitable multi-level system of support, they do not address racial equity in our schools, school funding concerns for special education, and do not address systemic factors of how schools and districts identify, plan for, and determine where and how students are educated that may also contribute to a denial of a Free and Appropriate Public Education for students with disabilities. Thus, although CEC High-Leverage Practice in Special Education may support improvement efforts, it is just one piece of a larger puzzle. Districts and schools are encouraged to use a continuous improvement process when exploring how best to support students with IEPs along with other marginalized groups of students. More information on the WI DPI continuous improvement web page.

Read more at:

Elementary Edition - Secondary Edition - District Level Edition

|

A number of advancements have occurred in special education in the past forty-four years after what is now known as the Individual with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) was signed into federal law in 1974. Today, many students who receive special education through an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) are provided with access and opportunities unimagined forty-four years ago as they are provided their civil right to a Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) in schools across the country. In our current digital age of instant information, social media platforms, and never ending stream of web sites dedicated to topics and practices related to special education one might think that knowing “how” to provide special education services is easier than ever. However, identifying what actually works in special education versus what is a current trend or well-designed marketing program has becomes harder and harder for those with a limited background in special education or those that do not have the time to analyze peer reviewed research.

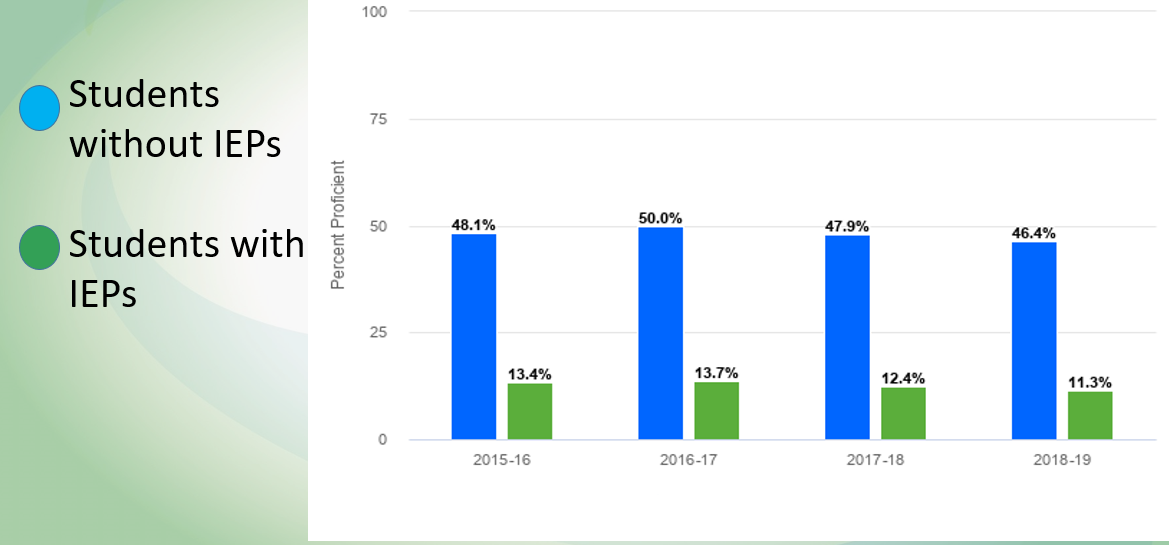

A number of advancements have occurred in special education in the past forty-four years after what is now known as the Individual with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) was signed into federal law in 1974. Today, many students who receive special education through an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) are provided with access and opportunities unimagined forty-four years ago as they are provided their civil right to a Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) in schools across the country. In our current digital age of instant information, social media platforms, and never ending stream of web sites dedicated to topics and practices related to special education one might think that knowing “how” to provide special education services is easier than ever. However, identifying what actually works in special education versus what is a current trend or well-designed marketing program has becomes harder and harder for those with a limited background in special education or those that do not have the time to analyze peer reviewed research. For some, the stagnation in outcomes for students with IEPs across the last several years has led to a sense of urgency to identify effective special education practices. Although we have advanced greatly from forty four years ago in providing access to grade level general education curriculum, instruction, and environments, the last several years of outcomes for students with IEPs have remained constant. That is, we have not seen the progress in closing achievement gaps for students with and without IEPs in areas such as graduation, academic outcomes, disciplinary removals, and access to the least restrictive educational environment that is still sought from landmark IDEA federal legislation. In Wisconsin and other states, additional factors such as more teachers leaving and fewer teachers entering the professional of special education, a greater focus on cross categorical special education programs resulting in less disability-specific knowledge for developing interventions, and reductions in special education funding, have further created the desire to identify high-leverage practices in special education.

For some, the stagnation in outcomes for students with IEPs across the last several years has led to a sense of urgency to identify effective special education practices. Although we have advanced greatly from forty four years ago in providing access to grade level general education curriculum, instruction, and environments, the last several years of outcomes for students with IEPs have remained constant. That is, we have not seen the progress in closing achievement gaps for students with and without IEPs in areas such as graduation, academic outcomes, disciplinary removals, and access to the least restrictive educational environment that is still sought from landmark IDEA federal legislation. In Wisconsin and other states, additional factors such as more teachers leaving and fewer teachers entering the professional of special education, a greater focus on cross categorical special education programs resulting in less disability-specific knowledge for developing interventions, and reductions in special education funding, have further created the desire to identify high-leverage practices in special education.