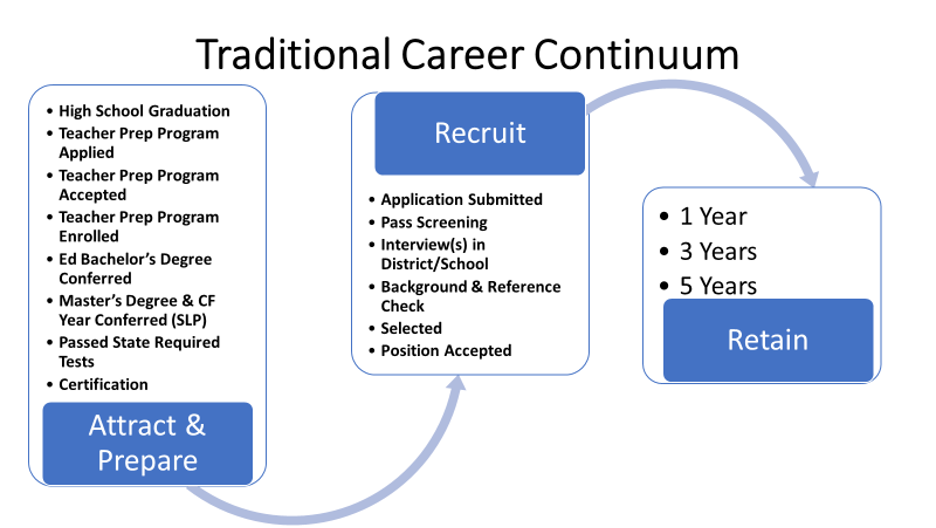

Staffing Challenges in Special Education and Related Services: What Building Leaders Need to KnowBy Barb VanHaren, Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction An EdWeek Research Center survey involving a nationally representative sample of 255 principals and 280 district leaders was conducted between June 29 and July 18. Almost three-quarters of the participants indicated an insufficient number of candidates are available for teachers, paraprofessionals, bus drivers, food service workers, and custodial workers positions this year. (Education Week August 1, 2022) Wisconsin is one of the forty-eight states reporting staffing challenges, particularly in the areas of special education, pupil, and related services. In August 2022, the Department of Public Instruction (DPI) surveyed school districts regarding staffing shortages for the upcoming 2022-23 school year. The survey generated responses from 333 local education agencies (LEAs). The subject area reported most frequently as having staffing shortages was special education (over 50%). Many future educators embark in a traditional pathway to licensure and employment in special education and related services. The following visuals depict that journey:

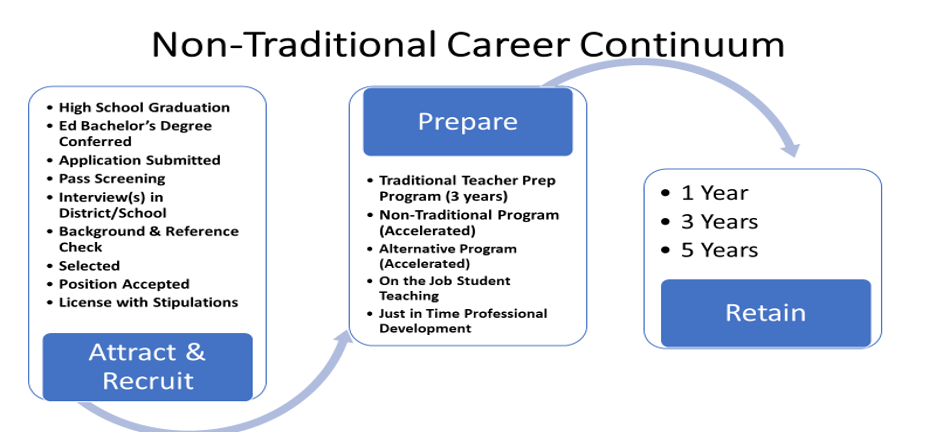

However, an increasing number of teachers entering the field of special education or related services take a non-traditional pathway and receive a license with stipulations (LWS). The non-traditional pathway shifts preparation from before the recruitment phase to after. Resulting in the need to provide alternative pathways and just-in-time learning.

Staffing challenges are exacerbated by high rates of attrition of special education teachers found to be 2.5 times more likely to leave the profession than teachers in general education (Smith & Ingersoll, 2004). New special educators are more likely than experienced teachers to leave their jobs. Some estimates suggest that up to 50% of new teachers leave in the first several years. Teachers who have received extensive preparation are more likely to use effective practices and stay in their positions than those who have minimal preparation. The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction (DPI) Special Education Team conducted seven regional focus groups regarding staffing shortages in Spring 2022 in order to garner input about the greatest challenges, what has worked well, and how DPI can assist by removing barriers and designating resources. There were between 8-12 participants from urban, suburban, and rural school districts and charter schools that were identified and invited to participate. Participants included building and district level leaders, special educators, related services providers, representatives from IHEs, et cetera. Below, we share both recommendations that emerged as well as the common themes they are aimed at addressing. RecommendationsFocus group participants offered valuable recommendations for attracting, preparing, and retaining special educators and related services providers. Some of the recommendations included: Attract: To increase the pipeline to working with students with disabilities, establish middle and high school student opportunities to work with students with IEPs; (e.g., youth programs, Special Olympics; Best Buddies, ASL courses, etc.). In addition, provide scholarships to high school graduates to participate in coursework related to the field of special education or related services. (i.e., Project PARA, Intro to Ed, ASL Classes) or to high school students pursuing careers in special education or related services. The provision of financial incentives was a common recommendation among participants. Incentives included scholarships or loan forgiveness; paying for tuition for coursework, course textbooks, release time, or degree completion for currently employed paraprofessionals and others to pursue a career in special education or related services. In addition, offering signing bonuses or salary advancements to cover tuition costs accrued prior to the initial pay period for first-year educators, along with housing assistance or relocation costs, was suggested. Finally, providing fee payments or reimbursement for costs associated with securing a substitute license was thought to be beneficial. Other recruitment recommendations included having the additional financial support to purchase software or contract with recruitment agencies to expand opportunities to make community and IHE connections representing candidates of color to diversify the workforce. Financial support to cover costs associated with participating in job fairs; utilizing teacher Websites and national publications (e.g., CEC); using technology (e.g., social media sites, virtual job fairs, electronic bulletin boards); hiring an external recruiter or advertising in local newspapers, radio, and television was also recommended. Prepare: Respondent recommendations for financial support to assist in the preparation of special educators included providing scholarships or loan forgiveness; paying for tuition for coursework, course textbooks, or degree completion for new special educators or related services providers. In addition, partnerships with IHEs were felt to be beneficial, such as establishing a tuition-free agreement or tuition reimbursement, offering paid release time (substitute) to pursue licensure or other professional development (e.g., attending classes, meeting with a mentor or coach, attend just-in-time professional learning opportunities), providing fee payments or reimbursement for alternative licensure programs (CESA, etc.) during the first year of employment prior to District Led Pathway or expenses related to a pathway to licensure (e.g., CCCs for speech/language pathologists). For areas without IHEs, recommendations included providing funds to special education and related services preparation programs to expand options for accessibility and availability in low-incidence programs, in IHE deserts, etc. Expansion options include the development of hybrid models, hiring additional faculty, offer evening and weekend courses. Finally, reducing the caseload and workload for new and LWS teachers by providing an extra preparation period per day to do coursework or work on “just in time” professional development was recommended. Retain: Building a statewide system of support for new/LWS educators was highly recommended, such as developing and implementing a statewide model induction program using a multi-level system of support based on the needs of special educators and related service providers in their nascent years. This system of support would also include just-in-time training, coaching, and networking opportunities for new/LWS educators. Participants recognized and recommended the need for compassion resiliency for new/LWS educators. Other focus group recommendations included the development of statewide guidance on caseload vs. workload, leveraging existing professional learning resources and training for all special educators and leadership, and assistance to districts to maximize IDEA entitlement funds to address recruitment and retention efforts. The participants recommended DPI continue to address barriers to certification and licensing requirements for special educators and the unique circumstances of related services personnel, including viable options to the FORT, supporting in-state preparation programs for low incidence areas, eliminate DSPS requirements for supervision of SLPs, create pathways for international candidates, etc. Finally, DPI was encouraged to initiate a statewide marketing/public relations campaign to attract individuals to the field of education and highlight positive educational stories. Summary of Findings: Common ThemesCommon themes emerged from the participants of the regional focus groups and the conversations from professional organizations and affiliations. The summary of findings organizes these common themes according to the Office of Special Education Program’s categories of attract, prepare, and retain. Attract: When addressing the challenges around attracting Special Educator and Related Services providers, respondents identified issues around the educator pipeline, growing your own initiatives, and financial concerns. Pipeline - Districts report high school graduates are not choosing education as a career, and IHEs report fewer candidates entering the field of education in general and in special education. Many referenced a lack of respect for the field, citing the fallout of Act 10, the pandemic, and polarizing political rhetoric as possible reasons for the decline. Districts need to be innovative in their recruitment strategies, casting a wider net for candidates. Grow your own (GYO) Programs - Districts report that GYO programs have shown the most promise in addressing teacher shortage.Paraprofessionals and others support staff already working in the district with students with IEPs are likely candidates for GYO programs. However, barriers continue to exist. For paraprofessionals quitting their jobs to go back to school is often not an option due to financial hardship on families and dependency on benefits. Financial Constraints/ConsiderationsParticipants reported migration as an issue, citing higher wages among neighboring or larger districts and in the medical field, making it challenging to be competitive. Some districts utilized ESSERS funds to provide substantive raises and reduce workloads making them more attractive to new hires. While IDEA entitlement dollars allow some costs associated with special education teacher recruitment and retention, small rural districts may not have the flexibility within their budget to offer loan forgiveness, signing bonuses, et cetera. Continual changing of positions or districts causes interruption to learning and doesn’t allow teachers to perfect their craft. Prepare: When addressing the preparation of special educators and related services providers, focus group participants shared concerns about access to institutions of higher learning, flexibility in licensure, and Wisconsin's requirements for certification. Availability and Accessibility of Educator Preparation Programs (EPP) - Various sections of Wisconsin are considered an IHE desert, impacting small rural districts when seeking candidates to hire. Some existing program structures at IHEs make it difficult for career changers to pursue a degree, which often requires a hybrid model or weekend and evening classes. Districts noted candidates with LWS are in need of just-in-time professional learning, particularly in the areas of compliance, High Leverage Practices in Special Education, Trauma Sensitive Schools, Culturally Responsive Practices, Mental Health, and challenging behaviors, in addition to traditional coursework. Flexibility in licensure - Wisconsin recognizes a cross-categorical (K-12) license, and most IHEs offer dual certification in general and special education. Districts value the flexibility this offers. However, districts also report a lack of preparedness for specific areas of special education. Many dual licensed teachers may begin their career in special education as a “foot in the door” and then transfer to general education in their first few years, causing disruption to programming. Certification requirements - A common theme across all stakeholders identified passing the Foundation of Reading Test (FORT) as a barrier and noted that portfolio equivalency is not always a viable option. This is particularly challenging for those using an alternative pathway and for those for whom English is not their first language. Teachers working with a License with Stipulations (LWS) are working during the day, taking classes at night, and then preparing for the FORT exam. Districts shared the need for more alternatives to demonstrate reading competency. In addition to test requirements, others noted on-the-job student teaching can be challenging, and that non-traditional students often miss critical methodology in their preparation. Teachers with LWS are often in the most challenging classrooms for their first years on the job. They come to the job with little to no experience and without “tools in their toolkit” to support students with IEPs. In addition to passing the FORT, participants shared the need for greater reciprocity for Out of State and International teaching candidates. Many IHEs report a lack of cooperating/supervising staff for practicum, clinical, student teaching, and intern placements. Some district staff reported an interest in accepting pre-service teachers but required administrative permission to do so. Others noted the need for incentives to do the extra supervision work. Many Cooperative Education Service Agencies (CESAs) offer alternative and accelerated licensure programs. This is an often utilized option, particularly in rural areas for LWS teachers. However, alternative licensure programs do not qualify for federal loans, leaving teachers of districts to pay the costs upfront. The area of related services provides a unique set of circumstances and concerns when addressing staffing challenges. As mentioned, there are no low-incidence or related service preparation programs in the state or in some regions of the state. Retain: Focus group participants cited the need to provide professional learning and coaching/mentoring, workload demands, and the climate or culture as impacting the retention of special educators and related services providers. Lack of coaching, mentoring, and just-in-time professional development. While growing your own programs has shown promise, many teachers enter the classroom with a license with stipulations and must complete their certification within three years. Participants regularly cited that coaching and just-in-time learning are needed for success once on the job. Participants also shared that administrators do not have time to coach and provide needed support for new and LWS staff. Without the proper preparation, many new and LWS teachers are not ready for the complexities of the job and do not have the necessary skills to be effective. This is particularly true for mental health needs and challenging behaviors. Without successful initial teaching experiences, many leave the profession within the first year or two, creating a cyclical disruption in staffing. Participants cited the need for better induction; onboarding, continued support through coaching and mentoring; and a network of support. Teachers with LWS need just-in-time professional learning in addition to their traditional or alternative preparation program. Participants from rural settings cited a lack of connection to the profession and job-alikes for professional growth. Participants from urban settings cited a lack of authentic representation in the teaching field. A common theme among all participants was the increase in mental health needs and challenging behaviors. Participants cited a need for more professional development and establishing or re-establishing proactive behavioral intervention structures following the pandemic. Caseload versus Workload. A consistent reason for the departure of special educators and related services personnel was caseload and workload expectations. Many participants referenced the differences between caseload (number of students assigned) versus the workload (the actual amount of time for direct and indirect services needed). Often the number of students on a special educator’s caseload does not reflect direct student services; evaluations; IEPs: preparation time; indirect services; directing paraprofessionals; consultation with general education, and other assignments. Factors contributing to the stress of an educator’s workload included the amount of paperwork and meetings, shortage of substitutes and paraprofessionals, and an increase in referrals following the pandemic. Attrition and lack of funding or viable candidates - vacancies go unfilled, and work transfers to caseloads of other staff. Novice and LWS teachers often struggle to manage the dual expectation as a first-year teacher and full-time student. Climate and Culture. The climate and culture of a school building, district, and community are critical in the job satisfaction of its members. When responding to reasons why special educators and related services providers leave the profession, participants identified a number of factors. Some participants listed a lack of administrative understanding and support for special educators. Many special education teachers and related service providers report to two supervisors, the director of special education/pupil services and the building principal, which add to the stress of the job. Many new educators are trained to support inclusive environments but often do not find their philosophies matching the service delivery model in their new district. In some situations, there is not an “ours” or collective responsibility belief upheld. Many participants also cited parental demands, social media, and polarizing rhetoric as impacting their desire to remain in the profession. For the complete Summary of Findings and other related information, please visit: Resources to Attract, Prepare, and Retain Special Educators and Related Services Providers For more information on maximizing IDEA entitlement funds to address recruitment and retention efforts, please see the following document:Leveraging IDEA Funds to Attract/Prepare/Retain Special Educators & Related Services Providers: Allowable Costs. |