Annotation and Personal InquiryBy Peg Grafwallner, Instructional Coach and Reading Specialist

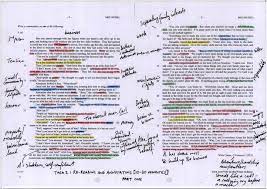

We want our students to interact with text in a personal way; to make inquiries and comments that demonstrate their learning in a way that makes sense to them. To comprehend text, one must deconstruct the text. That deconstruction begins with explicit directions from the teacher on how to read the text and make meaning from it. As an Instructional Coach and Reading Specialist, the first skill I teach students is annotation. Most teachers have their own way of teaching annotation. I’ve seen annotated text that looks like a coloring book, where colors designate meaning, understanding, emphasis, and so on. I’ve seen text that have “legends” in the corner, much like a map, where symbols mean key words, inferences, unknown vocabulary, and more. Let’s not make this more complicated than it needs to be. One way to kill reading is to tell students what they have to mark. Instead, let’s give students control over their reading. Let them relate to the text based on the questions they ask; let them personalize reading through their comments, and finally, let students make the text relatable by utilizing vocabulary that makes sense to them. In other words, students read for Questions, Comments, and Vocabulary (QCV), a method that all students can grasp and make their own.

In my book, Lessons Learned from the Special Education Classroom: Creating Opportunities for All Students an Opportunity to Listen, Learn, and Lead, I talk at length about the value of annotation. As an example, “It [annotation] helps students to interact with the text, it supports students in comprehending the text, and it gives students the opportunity to learn more about a topic they might know nothing about” (Grafwallner, p. 11). Annotation is a not just an academic skill; rather, it is a life-long skill that supports comprehension. I recommend teaching QCV within the first couple weeks of school. I also encourage all teachers to teach QCV; not just the English teachers or the Social Studies teachers. All courses – physical education, music, art – need to utilize this method so the student can transfer this skill from class to class. If the art teacher or the math teacher or the science teacher decides to teach their own system of annotation, it could be confusing for students to grasp that in some classes, annotation is done one way, but in this class, it’s not. If all teachers teach annotation the same way, students will quickly grasp how to annotate text. How to Annotate Step 1: Explain to students you will teach the skill of annotation; explain its purpose and value. Step 2: Distribute a short piece of informational text; ideally something that aligns to the lesson or unit you are teaching. Step 3: Read the title out loud. You want students to hear your thinking, you want them to hear you ask a question or make a comment. Create a question or comment about the title, write it next to a keyword that caused you to raise the question, or encouraged you to make a comment. Feel free to underline or highlight (choose one color throughout the text) that key word in the title. Step 4: Read the first two sentences out loud. Again, create a question or a comment. Write it next to the keyword or phrase. Underline or highlight, but don’t underline or highlight more than necessary. Students have a tendency to underline or highlight an entire sentence or paragraph when all they really need is a keyword or phrase. Get them in the habit of underlining or highlighting only what is necessary to make meaning. As you are reading, if there is a word within those sentences that you think students might not know, demonstrate how one might figure it out from context, or circle the word to show that you will need to look up the meaning. Step 5: Also, don’t forget to demonstrate that you are stuck. As you read the next sentence or two, show students that you don’t know what to ask or how to make a comment. Look at the Annotation Sentence Starters for help. Chose one question or one comment from the list. Take the time to tell students that it is okay to need support and to utilize the Sentence Starters if they need them. Step 6: When you have finished the short text, look up the unknown vocabulary words that you circled and write the definitions next to the unknown words. Briefly reread those bits of text again along with your annotations; making sure your annotations align with the new vocabulary word. The Benefits of Annotation Clearly, this process takes time. But when all teachers are invested in the same skill and utilizing the same method, students will grasp it quickly and begin using it right away. In addition, when students have mastered QCV, they will rely on their annotations for class discussion, test preparation, and purposeful writing. Students won’t have to re-read the text; rather, they will look to their real, relevant, and relatable annotations to join purposeful and meaningful class discussion. Think of QCV as a formative assessment. As the teacher walks around the room, students annotate. The teacher will be able to assess, in real time, if the reading is too difficult or too easy. If you notice a lack of questions or comments, or if the student is relying on the Sentence Starters exclusively, or if the text is drowning in circles, the teacher might infer the text is too challenging. In addition, if the teacher notices too few questions, too many “I knew that already” comments and little to no vocabulary circled, it is clear this reading is too pedestrian for students. Annotation can be differentiated based on the need of the student. Some students might not require any sentence starters and be able to, with pencil in hand, read and annotate. Other students, however, may need a little help. Consider offering this chart to those who may need support. Annotation Sentence Starters

In closing, consider annotation the first skill your students learn. We want to meet our students where they are, and as the year progresses, help propel them forward. Annotation offers students an opportunity for a text deep dive and for further research and exploration. Students have the opportunity to use their personal inquiries to learn about what interests them giving them a sense of control over, and a voice within, their own reading. References: Grafwallner, P. (2018). Lessons learned from the special education classroom: Creating opportunities for all students to listen, learn, and lead. Rowman and Littlefield. |